Publications

Enhancing Europe’s military capabilities

Russia’s brutal war of aggression against Ukraine has emphasised how important maintaining a credible deterrence and defence posture is – and how unprepared for this task most European states have long been. Against the backdrop of the war, the state of European defence has become a matter of genuine public interest. Consequently, there is rare political momentum to enhance Europe’s defence capabilities. However, for that to succeed, significant challenges need to be overcome.

The starting point for European defence is a difficult one. From the end of the Cold War until Russia’s first invasion of Ukraine in 2014, economic and security policy rationales led to major downscaling of European militaries in terms of both materiel and personnel. International crisis management was prioritised over territorial defence, and with the US providing the bulk of the necessary assets, Europeans were mostly content to play a small supporting role. Successive military operations duly revealed major shortfalls in European capabilities in critical areas such as command and control; intelligence, surveillance, and target acquisition; strategic airlift; as well as air-to-air refuelling.

On top of these long-known gaps now come the needs highlighted by Russia’s war in Ukraine. The war has shown the importance of long-range and precision fires, air and missile defence, electronic warfare, and drones. It has also served as a reminder of how resource-consuming long military campaigns are, emphasising the role of stockpiles, supply lines, and military industrial production capacity. Additionally, the Ukrainian experience has underscored the value of skilled and motivated military personnel.

Europeans have rightly committed themselves to supporting Ukraine’s legitimate fight against the invader. Being able to supply Ukraine while simultaneously bolstering their own defences will require massive efforts from all European states. At the same time, Europeans must also be better prepared to support security and prevent conflicts further afield. While military means alone are not the solution in conflict regions like the Sahel, enhanced capabilities could increase Europeans’ credibility and agency in places where they currently have little say.

Enhanced European capabilities are also needed for a more balanced and viable transatlantic relationship. Europe’s military weakness is a long-standing concern for the US and has gained even more importance recently, as the US strategic focus has shifted to the Indo-Pacific. While US capabilities and leadership remain essential for European security, the best way to secure continued US engagement is for Europe to adopt a bigger share of the burden. This would also make Europeans less vulnerable to potential changes in US domestic politics.

While US capabilities and leadership remain essential for European security, the best way to secure continued US engagement is for Europe to adopt a bigger share of the burden.

There are thus compelling reasons for European states to strengthen their capabilities. But this requires at least three things:

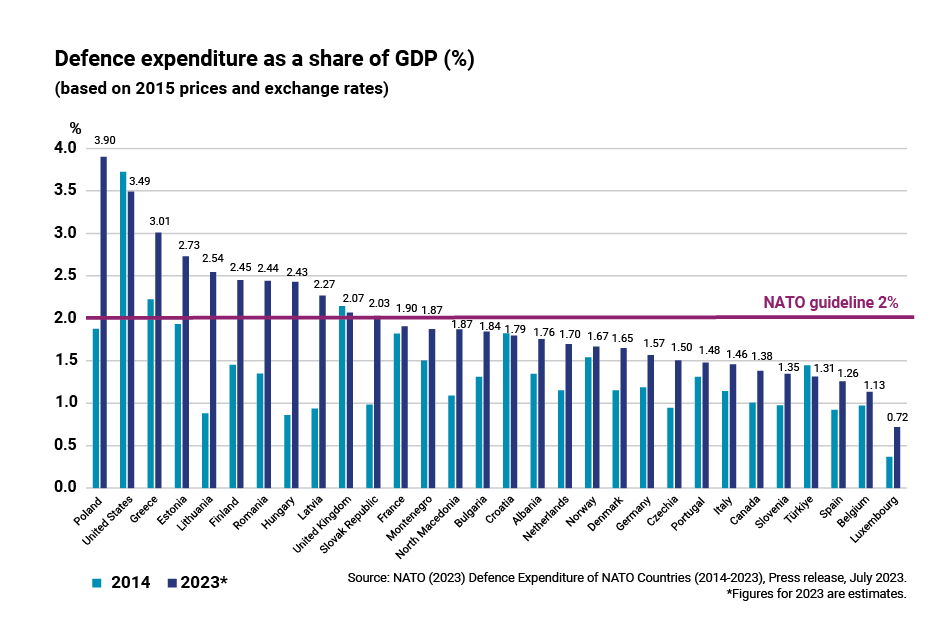

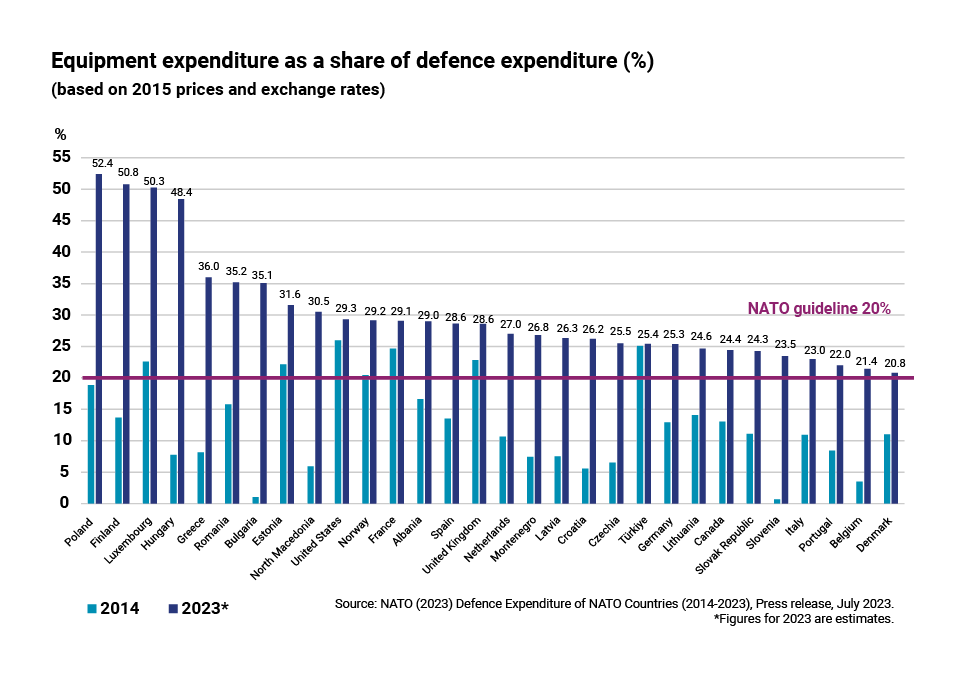

First, European states must commit adequate financial resources to defence and do so over the long term. European defence budgets have been on the rise since 2014, and the latest developments suggest that this trend will continue – but there remain significant differences between European states and justified doubts about the durability of their commitments.

Second, Europeans need to agree on clear priorities and a fruitful division of labour. Enhancing European capabilities is a long-term undertaking, and all issues cannot be addressed at once. Moreover, it does not make sense for everyone to focus on the same things. Instead, European defence needs to be seen as a collective effort in which different actors can assume different roles.

Third, Europe’s defence industry needs to be brought up to speed. Currently, it is characterised by both fragmentation and inefficiencies, which result from the European states’ tendency to favour national solutions. The industry also faces a shortage of skilled workforce and limited access to the necessary materials and components. Ramping up production will thus take time and sustained efforts.

Europe’s defence industry needs to be brought up to speed. Currently, it is characterised by both fragmentation and inefficiencies, which result from the European states’ tendency to favour national solutions.

To tackle all the mentioned challenges, cooperation and coordination between governments, armed forces, and defence companies in Europe and across the Atlantic are a necessity. Both NATO and the EU have a central role to play in all of this.

NATO’s renewed defence investment pledge (2% of GDP not a ceiling but a floor) remains the most important political instrument to usher European states to provide the necessary funds for enhancing their capabilities. Meanwhile, NATO’s Concept for Deterrence and Defence of the Euro-Atlantic Area (DDA) as well as its Defence Planning Process (NDPP) should guide the Europeans’ efforts to do so, laying out concrete priorities and requirements.

The EU, for its part, provides useful institutional and policy frameworks like Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) as well as potentially helpful financial instruments, such as the European Defence Fund (EDF), the European Defence Industry Reinforcement through Common Procurement Act (EDIRPA), and the European Defence Investment Programme (EDIP). Through these, the EU can incentivise cooperation among European governments and defence companies. Furthermore, the Union possesses regulatory power to influence the European defence industry and market.

Finally, various bilateral, trilateral, and minilateral formats of defence cooperation can make an important contribution to enhancing European capabilities as well. As for the US, it can best support this process by remaining engaged in European defence while simultaneously pushing Europeans to do more for their own security, as well as by adopting a pragmatic attitude towards European defence cooperation efforts.

Together, it is possible for Europe to make the most out of the current momentum and solve its long-standing capability predicament.

GOING FORWARD:

» In the context of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, there is rare political momentum to address the existing shortfalls in European defence capabilities.

» Europe needs enhanced defence capabilities to strengthen its deterrence and defence posture while simultaneously meeting Ukraine’s urgent military needs, to support security and prevent conflicts in other regions in and beyond Europe, and to contribute to a more balanced and viable transatlantic relationship.

» Three issues will be of crucial importance in the quest for enhancing European defence capabilities: committing adequate financial resources to defence over the long term; agreeing on clear priorities and a rational division of labour among European countries; and solving the multiple issues that hamper the functioning of the European defence industry. » For Europe to succeed in its efforts, cooperation and coordination between governments, armed forces, and defence companies in Europe and across the Atlantic are a necessity.

» Both NATO and the EU have a crucial role in strengthening Europe’s defence. NATO remains the primary organisation for collective defence and deterrence for the Euro-Atlantic area. The EU, for its part, offers useful institutional frameworks, financial instruments, and regulatory power to shape the European defence industry and market.

Tuomas Iso-Markku is a Senior Research Fellow at the European Union and Strategic Competition research programme at FIIA. Iso-Markku’s area of expertise includes the EU’s role in security and defence policy, European security and defence cooperation, EU-NATO relations, German politics, Finnish EU policy, Finnish foreign, security and defence policy, and party politics in Europe.

Iro Särkkä is a Senior Research Fellow in the research programme for Finnish Foreign Policy, Northern European Security and NATO at FIIA. Her areas of expertise include Finnish, Nordic, French and European foreign policy, multilateral security frameworks, NATO and the EU, as well as questions of political behaviour. Recently, her research interests have included studying and conceptualising national identity change in small states, securitisation theories and Nordic security.

This article has previously been published as part of the Helsinki Security Forum 2023 report.

Helsinki Security Forum 2024 addresses the need for European total defence

The third annual Helsinki Security Forum (HSF) will be held on 27–29 September 2024. This year’s conference is titled Towards...

for HSF Blog

Rejecting Russian Spheres of Influence

The EU has rejected the language of spheres of influence in favour of an international order based on common rules...

for HSF Blog

Reverberations in the Indo-Pacific of the War in Ukraine

Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine has had significant ripple effects in Indo-Pacific security dynamics and ongoing great-power competition.

About the author

Tuomas Iso-Markku and Iro Särkkä

Senior Research Fellow, FIIA

Tuomas Iso-Markku is a Senior Research Fellow at the European Union and Strategic Competition research programme at FIIA. Iso-Markku’s area of expertise includes the EU’s role in security and defence policy, European security and defence cooperation, EU-NATO relations, German politics, Finnish EU policy, Finnish foreign, security and defence policy, and party politics in Europe.

Iro Särkkä is a Senior Research Fellow in the research programme for Finnish Foreign Policy, Northern European Security and NATO at FIIA. Her areas of expertise include Finnish, Nordic, French and European foreign policy, multilateral security frameworks, NATO and the EU, as well as questions of political behaviour. Recently, her research interests have included studying and conceptualising national identity change in small states, securitisation theories and Nordic security.